Small Silent Voices (2024) is a project rooted in an ongoing exploration of landscape, botanical life, and geological time. In this new series, I travelled north, up the backbone of the country, to the Scottish Highlands, a place shaped by older, darker forces, where the land holds a deeper geological memory. What unfolded was not simply a geographical journey, but a conceptual and temporal one, from my home in the relatively young chalk hills of southern England to a place of ancient rock formed deep in the Earth’s crust more than two billion years ago.

For Come, See Real Flowers of This Painful World (2020), I walked and collected and photographed native wildflowers from the South Downs, a landscape created from the white, alkaline chalk formed from the remains of coccoliths during the Cretaceous period. In Glenelg, I encountered some of the oldest rocks on Earth, Lewisian gneiss and Moine schist; ancient, metamorphic formations folded deep inside the Earth. The soils derived from this bedrock support a flora quite different from that of the chalk Downs. However, the Highland wildflowers also grow with a quiet resilience shaped by their mineral origins, climate, and place.

While the final images are central to the work, my practice begins long before the camera is involved. The process itself - walking, researching, folding, drawing, and making is equally significant. Beginning with detailed botanical research, I mapped where particular species thrive, under what environmental conditions, and at which points in the season they flower. In parallel, a small ericaceous garden was constructed at the site of my South Downs studio, a chalk-rich place markedly different in soil to the Highlands. I brought together plants such as Ragged robin, Meadowsweet, Bog bean, and Lesser spearwort, all species that prefer boggy, peaty, water-retentive soils and I grew them in a deliberately constructed environment far removed from their native habitat. This cultivated plot functioned both as an ecological experiment and a quiet performance piece, raising questions around the human impulse to relocate, contain, and aestheticise nature. It was an act of intimacy and distance, themes that run throughout the work.

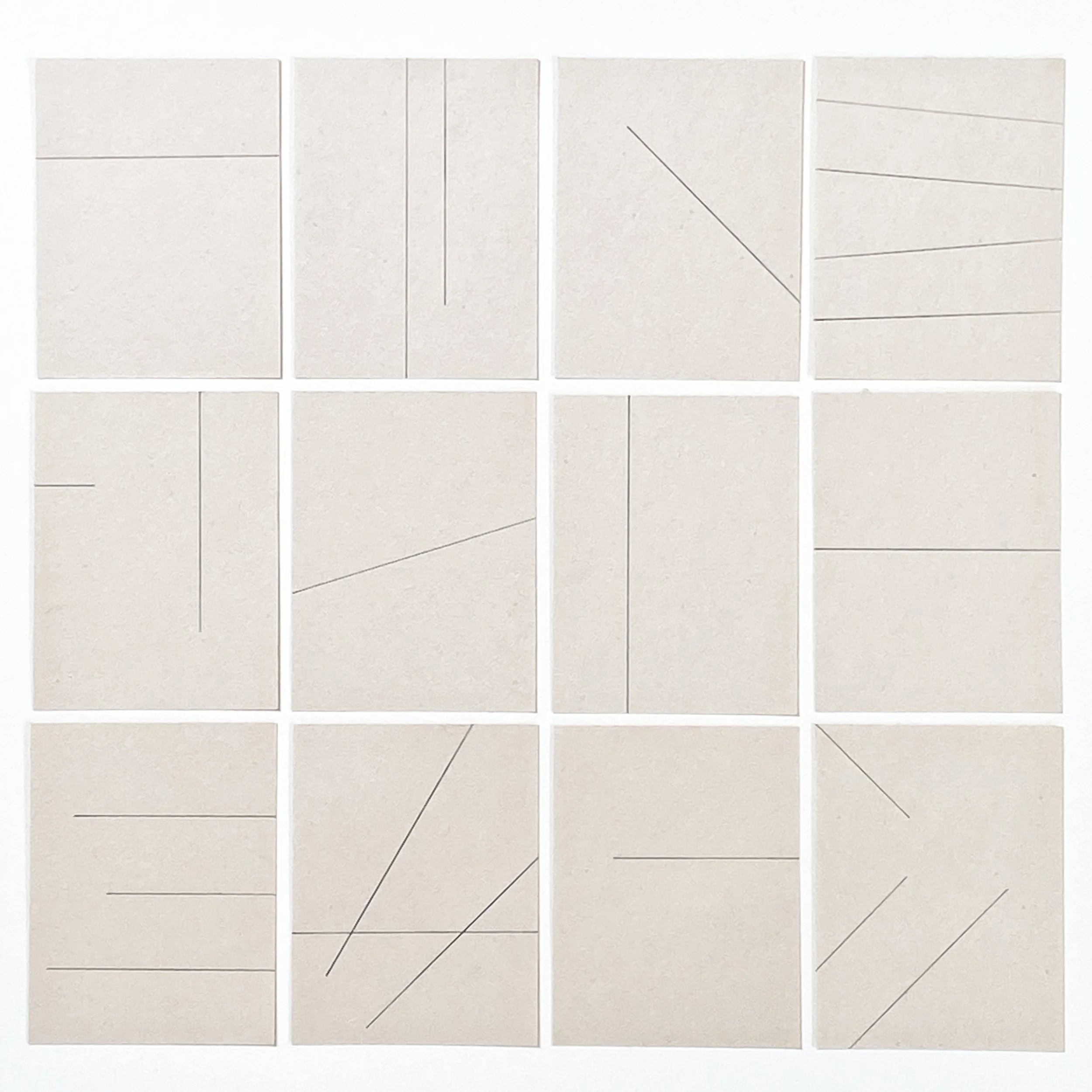

Walking, as in my previous project, is both a research method and a form of connection. I began by photographing rock surfaces, focusing on their folds, lines, and layers, the visible traces of tectonic activity and time. The Highlands are a landscape formed through immense pressure, folding, and uplift. Their very structure speaks to ancient tectonic collisions, continental drift, and the reshaping of the Earth long before any human presence. These markings became the basis for simple line drawings made in graphite pencil, a material itself drawn from rock. From these studies, I folded larger sheets of paper along the lines I had traced, referencing both geological folding and the act of mark-making. The process of folding was repetitive and meditative, an echo of the walks that shaped my earlier Downland work, and of geological movement itself. The folded papers were then painted, mixed to match the greys, pinks, and blacks sampled directly from the rock on Glenelg beach. These painted surfaces became backgrounds for a series of photographic portraits of wildflowers collected in and around Glenelg. Each image places the plant in dialogue with a constructed geology; part paper, part pigment, part trace thus exploring the continuity between biological cycles and geological time.

Throughout this work I have been preoccupied with time, the vast duration required to fold rock, to weather stone, and the more immediate rhythms of a flower’s growth or a moment of close attention. I have also continued to explore the idea of connection between geology and botany, human gesture and natural form. The folds in the paper become echoes of the ancient curvature found in strata, while the contrasting environments between the north and the south, the acid and alkali, micro and macro, past and present highlight the fragile inter dependencies within ecosystems shaped by rock, climate, and time. These creases and folds become visual metaphors for connection, for the passage of time, and for the traces we leave behind. Folding becomes a way of registering time - compressing, opening and closing and repeating.

The title comes from Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, where she writes: “In the mountains, I see flowers like a thousand small, silent voices, each one part of a vast harmony.” The idea of small voices, quietly connected to something much larger is central to this work. The wildflowers, like the folds in the paper and the folds in the landscape, speak of place, of movement, and time. They are not just decorative, but integral, quiet witnesses to transformation. Wildflowers do not exist in isolation, they are born of soil and stone, shaped by wind and water, and dependent on a long history of environmental conditions.

Fold markings, 2023 (graphite and paper)

In this series I draw visual and conceptual connections between botanical illustration, geological mapping, and lived experience. The creases in paper recall worn maps, archival pages, and field guides, the tools of documentation that bear the marks of use, handling, and human connection to the land. Just as ancient rock holds the memory of past continental collisions, the folded paper records the gestures of the hand. It is both structure and mark, process and result. They ask us to consider the often-invisible systems that shape the visible world, and to pay closer attention to how things grow, survive, and endure. We are shaped by the landscapes we inhabit, just as the rocks, soils, and plants are shaped by forces far older than us. My journey from Sussex to the Highlands traces not only a physical route across the country, but a passage through geological time. My stay at Taigh Whin in Glenelg enabled me to travel back to moments of mountain- building and continental drift, to the folding of the Earth’s crust, and to the soils and plants shaped by that history. Kathryn Martin, 2024

This project was made possible by the kindness of Turadh, which offers spaces of rest, reflection, and renewal to all those working for the common good in Scotland.

Meadowsweet ii, Tormentil, Rowan, Cross leaved heath, Welsh poppy, Valerian, Foxglove, Meadowsweet, Red clover, Eyebright, Bog Asphodel, Greater Birdfoot trefoil, Spotted heath orchid